Co-working facilities are sprouting up like weeds as city building owners embrace the concept and freelancers, startups and even larger companies become “members” to occupy millions of square feet in New York and around the country in these collaborative environments.

Already, the industry has over 16,000 co-working spaces around the globe; that number is projected to grow to 40,000 by 2018. With 900,000 people now working out of these shared environments, the total will expand to 3 million by 2018.

Co-working sites can cost as little as $25 for a day pass, but escalate as members rent dedicated desks and go up through the thousands per month for some of the lockable private offices that can accommodate numerous employees.

While some may feel like frat parties with free-flowing beer, others have created comfy environments for people of all ages, out-of-towners, women, nursing moms and even larger corporations.

Real estate executives Morris Levy and Richard Beyda founded The Yard in 2011 across from McCarren Park. (It’s where Uber was eventually nurtured.) The Yard is now opening its seventh location at 116 Nassau St., with six more on the way that will include 510 Fifth Ave.

Levy says the Yard is “all about hospitality,” but to provide privacy, there are solid walls between small firms. They also rotate works by local artists on the walls of the open spaces. Some of the locations also have well-used outdoor areas, and all are pet-friendly.

Industrious was founded by James Hodari in Chicago after he was too embarrassed to hold an important meeting at his local co-working space and ended up in a coffee shop instead.

His initial 17,000 square feet had room for 62 companies and 600 applied.

“We felt it was very clear that this would move beyond freelancers and startups and we should get ahead of this,” he says. “Creating a comfortable environment became paramount.”

They now have a dozen spaces in 11 cities, including New York, and are planning to open in another dozen cities. “We found we are equally successful in any type of city,” he said. “This is where the workplace of the future is going.”

Their interiors are “understated, genuine, welcoming and high quality” and focus on spaces flooded with natural light because research shows it makes people more productive.

“We are trying to be a hospitality company, and our value proposition is that we will make your teams excited and proud to come to work,” Hodari says.

“Once companies have tried out using co-working, we see very few going back to traditional office settings because the employees want it. It is very hard to see what events would trigger a reversal of that trend.”

For that reason, Industrious is already hosting many large businesses like Pinterest, Spotify and Lyft who have a high-quality headquarters environment but can’t offer that for a 20-employee regional office.

Hodari says, “We want to feel inclusive, and it should feel just as comfortable for someone in their 70s or a young mother or someone who is not entering a beer-pong tournament.”

You also won’t find a ping-pong table at Alley, which was created by Jason Saltzman after being uncomfortable in spaces he too rented as a startup owner.

He started in 2012 with 16,000 square feet at 500 Seventh Ave. and the space took off after Hurricane Sandy when Saltzman’s email stating they had desks available went viral and almost 800 people showed up. He rented chairs and tables to accommodate the crowds bumped from their own offices and never looked back.

While there is an application process for membership, Saltzman says they want people of every age, race and ethnicity and the “process” is designed to “keep out a**holes.”

“If you are a good person, we want you,” he insists.

To encourage interaction, Alley’s private spaces are also made of soundproof glass. “You can see what people are working on,” he explains.

Early on, members wanted more open space. But now, he says they want their own rooms and privacy. A new 40,000-square-foot spot in Chelsea at 119 W. 24 St. has plenty of private offices.

Alley also created a state-of-the art lactation room for nursing mothers that has been featured as one of the top in the county.

“People need mentorship and need access to people; they need investments and a support system,” Saltzman explains. “It is not only a community. We throw a ton of events and programming — with local partners, with the startups themselves — and have hackathon workshops.”

Saltzman is also very engaged with the members. “I get to give them advice and connect them with other people,” he says.

A new partnership with Marriott will bring those activities and workshops into its AC Hotels business centers and other spaces.

“The AC owners want to use their spaces to tap into these entrepreneurs,” Saltzman explains. “The piece missing was the collaborative aspect.”

He has also just opened a 5,000-square-foot EdTech Accelerator powered by StartEd for NYU’s Steinhardt school at 35 W. 4th St., albeit just for students, who will also have access to other Alley locations that are open 24/7.

‘We are tapping into the next generation of entrepreneurs.’

– Jason Saltzman, founder of Alley

“We are tapping into the next generation of entrepreneurs,” Saltzman says. “We are hosting an accelerator program and are focused on education with StartEd, which is an accelerator for early-stage education companies.”

Christophe Garnier, a Frenchman with 17 years of startup and tech experience both abroad and in San Francisco, founded Spark Labs in New York to focus on non-US and out-of-town tech firms that want collaborative support within a more familiar culture.

It will soon have 20,000 square feet at 25 W. 39 St. along with a spot at 833 Broadway.

These companies are typically already successful in their home countries or cities, Garnier says. Venture capitalists including White Star Capital, Rubicon Venture Capital and FirstMark Capital often provide funding.

Partnerships with IBM, Amazon Web Services and Salesforce for Startups also provide tech perks and programs to Spark Labs members worth thousands of dollars.

Textile designers have their own co-working facility in Fuigo, which was created earlier this year in 18,000 square feet at 304 Park Ave. South.

Brothers and co-founders Maury and Mickey Riad call it “Designer Disneyland.” A $4 million installation devotes a third of the space to expensive resources and samples. “We created an ecosystem so that anything the interior designer needs can be found in this collaborative,” Maury Riad says. “We are facilitators.”

Their co-founder Bradley Stephens designed the interior, which has workspaces, a kitchen and conference area. Membership levels start with access to its cloud-based project management software and on-site resources and rises to include a dedicated business concierge and a studio coordinator plus lockable offices.

The co-working behemoth WeWork now has 1.87 million square feet open in New York City alone, with 2.5 million square feet on the way. There are 25 outposts in Manhattan with 29 planned, four in Brooklyn with six more coming, and one in Queens with two more in the works.

They are also seeing more later-stage companies become members for reasons that vary from simply needing some short-term transient space to having a central location for a dispersed sales force. For some, it is more economical for a satellite office.

“We also increasingly see it is a way to outsource their whole real estate effort,” says a WeWork spokesman. “Their expertise is not necessarily there.”

WeWork is also trying to shake its frat house image. Its online magazine for members, Creator, now has a new section called “40 over 40” to highlight some of its middle-agers. “We see a whole host of cool people and they are going against the grain of what a typical WeWork member looks like,” the spokesman says.

“A lot of our clients started off in co-working spaces,” said Ben Brachot of Dwight Funding, which helps support the day-to-day capital needs of these companies.

Those that move out, Brachot says, want to define their own brand and culture.

Brands with more than 15 employees often leave to rent their own spaces. But that is now the fastest-growing segment of WeWork’s business, the spokesman said. Larger co-working facilities are able to provide the branding and identity for those that want some privacy, but also want to keep flexible leases and remain part of the community.

So far, about one-third of WeWork’s 70,000 members around the world have 15 or more desks. In Hong Kong, HSBC just rented 300 desks.

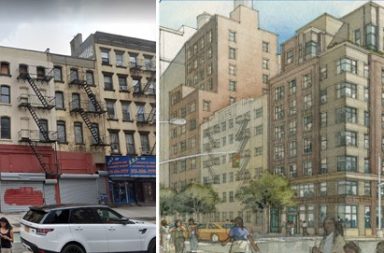

WeWork is now considering buying its own space and buildings, even as its original business model centered on leasing space pioneered the growing shift in workplace culture worldwide.

Other companies are catering to the co-working graduates. David Levy, a principal of Adams & Co., is building out furnished high-end suites, a conference center and lounge at 110 W. 40th for those that have outgrown co-working space and want privacy but with some interaction. The asking rent is $75 per foot and most spots have already been rented.

In the Madison Square Park area, the Kaufman Organization is creating turnkey prebuilts that are being occupied under three- to five-year leases by tech companies that have grown out of co-working spots and want to be on their own.

But beware of consolidation. Some smaller co-working spaces are now looking at competitors to take over because they are not able to make the economics work.