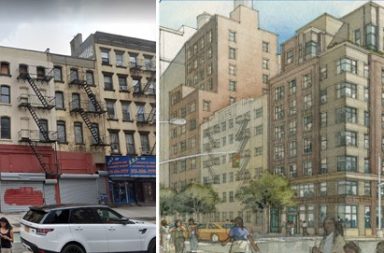

Developers and lenders are fretting over the changing and expiring affordable rental development programs.

For years, the 80/20 program has created housing with 80 percent of the apartments renting for market rate. Those rents then subsidized the 20 percent of the units that paid much lower rents. The entire development had been eligible to be financed with tax-exempt bonds and low income housing tax credits. Not any more.

Most worrisome is the June 15, 2015 sunsetting of the state law that enables the 421a tax abatement. This allows developers to qualify for a 20 to 25 year property tax exemption on the value of the new construction. Depending on the location, the exemption burns off over time until full taxes are paid.

But to qualify for 421a, a developer must have a fully developed set of plans, pull a new building permit and have a footing in the ground prior to June 15, 2015. The clock has run out.

Drew Fletcher, Managing Director of the Greystone Bassuk Group, said, “A combination of these benefits balanced out the economics that allowed developers to achieve a minimum yield, and for investors to take construction and lease-up risk, and build these products.”

If land costs $350 per foot, total costs to develop a 300- to 400-unit rental tower are roughly $1,000 per foot. More recent land purchases in Manhattan are being bid up over $600 per foot and even $800 a foot or more. At this level of land pricing, any apartments that are developed cannot be rented cheaply so the building must be designed and sold as high-priced condos.

“When you cross $250 to $300 a buildable foot it becomes a condo site,” explained James Kuhn, president of Newmark Grubb Knight Frank. The price per foot for selling a condo also provides far more of a payback over the development costs than simply leasing an apartment for rent.

“There is no viable [rental] scenario without 421a,” Fletcher insisted. Because the current 421a tax benefit “burns off,” he said any new legislative program that requires permanently affordable units should give them a permanent tax abatement.

Allowing non-union construction could also reduce costs by 20 to 25 percent.

Gary Rosenberg, a partner with Rosenberg & Estis, says if the rent on the market-rate apartments is high enough, developers can afford to build so long as they obtain the property tax abatement. “Where the rents aren’t that high, you want to encourage construction, period,” said Rosenberg of the outer boroughs.

Broker Eric Anton, senior managing director, HFF, says the city has to be careful that new programs and requirements don’t disincentivize developers from building low income housing. “It’s nice to want low income housing but someone has to pay for it,” Anton said. “The rents are so painfully low that it doesn’t cover anything.”

Any development that has to go through the land review process, like the recent Astoria Cove project, may be in trouble, these experts say. “It’s hard to underwrite new projects without knowing what the city will want,” said Anton.

The city required the Astoria Cove project to include a 25 percent affordable component but also cut off the developer’s ability to use public financing for it. Two percent of the apartments will also be set aside as moderate income but can access Housing Development Corp. financing. Union labor is required for all construction. “That decision sent a chill through the development community and the lenders,” said one expert on condition of anonymity. “Where is the appreciation for the economic realities and the minimum return to induce construction?”