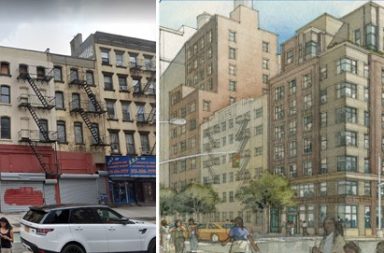

The City Council and Mayor de Blasio can high-five all they want, but real estate experts believe the new Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) policies that require affordable units to be interspersed throughout buildings — while so far, not providing any real estate tax breaks in return for the lower rents — will put a damper on development.

“As much as people want to take the opportunity, I don’t know that the mayor’s new plan will stimulate the demand,” says Steve Hochberg, a partner with law firm Stempel Bennett Claman & Hochberg. “It affects the cash flow and the ability to generate revenue because the overall expenses with full taxes are too high.”

Venable lawyer Daniel Bernstein agreed that, while a current pipeline will keep developers and construction workers busy, without a property tax break similar to the sunset 421-a program, mixed-rent buildings will be missing.

“You will only see the 100 percent affordable or some of the lower Mandatory Inclusionary Housing income brackets with significant subsidies,” he predicts.

That’s because the apartment buildings pay 20 percent to 30 percent of gross residential rents as property taxes but, under the new MIH rules, they still have to make them permanently affordable, Bernstein explained.

“The trade-off is that, if the MIH is on-site, in the more expensive, stronger markets, there is a higher cost to that affordable unit, whereas if it is developed off-site, it can be produced at an affordable price.”

As the affordable units are now legally required to be mixed within the buildings — and not have a separate entrance — developers have to consider this as it affects the buildings’ value and future income stream, Bernstein says.

In my opinion, this “poor door,” as first embarrassingly anointed by this paper, should really be known as the “lucky door” as those snagging new apartments in highly contested lotteries have won a lifetime of cheap rents for themselves and their successor families.

Sure, in the past, if you interspersed a dozen units into a new project, they were likely to be at the bottom or on a side without great views, but they were still in new buildings with new appliances, bathrooms and kitchens at a highly discounted rent.

But when developers create 500 apartments and 100 of them are affordable, it makes economic sense to lump them at the base of a project with their own lovely entrance, lobby, elevators, community rooms and laundry rooms. When completed, a different company with expertise in affordable housing and its reporting requirements can manage or own this building within a building. It would have its own address, block and lot and be taxed separately — and be eligible for various grants and programs.

The luxury apartments above, with their own address, block and lot, and paying two, three or more times as much in rent, can also be managed separately and have amenities like full gyms, pools and pet spas supported by the much higher rents.

As an “exit strategy,” the developer may sell the fully leased project to a company that can run it as a market rate rental or even sell it again to a sponsor to be converted into a luxury condominium.

Along with a new 421-a type property tax program to ensure a public subsidy for the affordable units, the value of living in a better area — but with a “Lucky Door” as a trade-off — should be revisited by the legislature.

Shake Shack is coming to an underground concourse inside Penn Station.

The Vornado Realty Trust-owned retail corridor that includes Kmart is now upping its retail game to provide better stores with nicer storefronts that service commuters and the neighborhood while dumping the older and schlockier outlets.

The 10-year lease had an asking rent of $500 per square foot for the 2,489-square-foot store.

Andrew Goldberg, Matt Chmielecki and Preston Cannon of CBRE represented the now-public company started by Danny Meyer that serves up burgers, fries and beer. Ed Hogan represented Vornado, in-house. The concourse asking rents are still in the $500s per square foot. The parties declined comment through spokespersons.

Vornado has already instituted new design guidelines for its north side of this Penn Station corridor and brought in Magnolia Bakery, Pret A Manger and Duane Reade. Upstairs on the street level, it is also bringing in a better class of tenants and food, such as its raved-about Pennsy, as other leases expire.

Here’s another opportunity to own a building housing a landmark city eatery. The four-story corner mixed-use property at 1424 Avenue J, where the acclaimed Di Fara Pizza celebrated its 50th anniversary last October, is now on the market.

As a mayoral candidate, Bill de Blasio declared it the best pizza in the city, and its long lines are legendary.

The low-rise building on the end of the block is typical in Brooklyn’s Midwood neighborhood. The 1911 four-story property includes three 2-bedroom and three 3-bedroom stabilized rental apartments.

The DeMarco family’s Di Fara Pizza takes up the prime corner, while Di Fara Dolce FATTS Cafe and Sweet Shoppe on East 15 Street, along with a sub shop and a shoe repair shop, round out the property.

Near Brooklyn College and the Flatbush Avenue Junction hub, the area has retail rents of $75 to $95 a square foot with some month-to-month tenants paying more.

Shulem Paneth and Eli Matyas of GFI Realty Services have the listing from the current ownership with a price target of $3.975 million.