Once a way to quickly lease a floor or two in an office building, shared work spaces have become so hip that businesses are even leasing them for their entire staffs or as satellite offices. That means, in more and more cases, communal offices are competing with traditional commercial real estate properties for the same tenants.

So far this year, 16 co-working firms have leased a combined 664,000 square feet, says David Falk, tri-state chairman of Newmark Knight Frank.

WeWork, he adds, is the fastest-growing company in New York. Soon to have nearly 3 million square feet, they are also the No. 2 space occupier in the city, just behind JPMorgan Chase.

As of April 5, there were 204 co-working spaces in the city, according to New Worker magazine.

“Co-working is trying to scale very fast to be more competitive,” says Peter Turchin, vice chairman of CBRE.

There is good reason: The Yard, a co-working chain founded in 2011 in Brooklyn, claims it has a 40 percent profit margin. Although companies pay more per square foot at The Yard than they would by leasing directly, co-founder Morris Levy says they still save money. “It’s still about 30 to 40 percent cheaper per person than taking their own space,” he says.

That’s because businesses in co-working spaces don’t pay for common areas like halls, kitchens and bathrooms, certain insurance, or the loss factor (which is nearly 30 percent in New York).

Levy adds, “The tenants are also not paying for buildouts, internet, cleaning services and supplies or the employee manning the front desk.”

In addition, they also pay for fewer square feet and shorter time periods — whatever is needed. “They are paying for flexibility,” says Bob Savitt, president of Savitt Partners.

About seven years ago, Savitt Partners opened its own co-working facility, Space 530, in 30,000 square feet at its 530 Seventh Ave. office tower, which it leases to a few small companies. But Savitt is not looking to open more such facilities as they are management-intensive.

Five years ago, the average co-working site was less than 30,000 square feet. Now major players are taking 70,000 to 150,000 square feet at a time — and more. WeWork has leased 222,000 feet at the Brooklyn Navy Yard’s Dock 72 and is a co-developer of the 675,000-square-foot building.

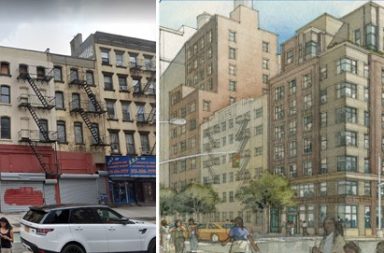

Co-working sites are now absorbing a lot of space. “They are taking down entire buildings for branding and image,” says Falk. For instance, Jay Suites just net leased the entire 90,000-square-foot building at 15 W. 38th St. for its ninth location. Concentrating on luxury private suites, the space will soon include a conference center and coffee shop.

Since many employees are spending more time out of their offices, companies are also rethinking their space needs.

And as co-working expands around the world, global companies are also putting down Manhattan anchors. For example, the 128-location UCommune, founded in China, just opened its doors within Serendipity Labs at 28 Liberty St. The 34,000-square-foot space has a serene vibe with glass-walled offices and private areas.

London-based Instant Offices matches global businesses with shared offices around the world.

Instant is seeing some tenants expand out of co-working and into their own fitted-out spaces, says Michelle Bodick of Instant Offices’ parent company, Instant Group.

London and Berlin are now filled with numerous co-working places, Bodick says, and to grow their own businesses many of them want to expand to New York.

The rise in both US and international co-working offices means that corporations have quickly realized they can set up regional offices without the headache of long-term leases, buildouts and fixed sizes despite headcount growth.

These short-term “enterprise” deals also allow companies to avoid adding such leases to their balance sheets. Under new accounting rules, companies will be required to do so for any lease over one year.

The Yard is now focused on marketing to these “enterprise companies,” which it defines as using 12 or more desks. Currently, The Yard counts 560 such firms as members, with Uber and Blue Apron as past clients. At its Flatiron North location at 246 Fifth Ave., the global strategy firm Accenture occupies 31 desks in more than 2,000 square feet.

Toronto-based social content provider Diply chose the same Yard location for its first US office, which it opened in 2016 with eight employees. The president and chief revenue officer of Diply, Dan Lagani, says that for a high-growth technology business, real estate leases present tough decisions.

The Yard made it easy to open stateside, Lagani adds, and expand to 28 employees. Now the hallway to their own corner office is lined with Diply logos. “It’s a good, upbeat, happy space,” he says.

While hundreds of co-working locations are competing for tenants, Turchin says, “They are also competing with [building] owners” for the same tenants.

“Co-working sites have leased a lot of space, but now they are starting the enterprise model and going after tenants,” Falk agrees. “Landlords haven’t really felt the competition, but it’s present and more prevalent.”

But some owners are already feeling a drop in the number of tenants seeking smaller spaces.

“The WeWorks of the world are competing with the landlords,” Savitt says. “There is less demand for small space.”

Brokers are also evolving to participate in such transactions. “Co-working [spaces] are paying the brokers and opening up lines of communication,” Falk says. “It is all changing.”

But co-working sites focused on the enterprise model are more exposed to a downturn in the economy, Falk warns, “If the companies [renting larger spaces within co-working venues] got hit badly, there would be an effect,” he says.