It’s disturbing to imagine, but gun violence in the workplace and public spaces is on the rise. Twenty-five years ago, active shooters in the US were rare, but now there are about two to three incidents a week on average across the country.

If the unthinkable happens, what do you do?

According to Officer Christopher Mazzey from the New York Police Department (NYPD) Counterterrorism Bureau, it’s time to get to or create a safe space.

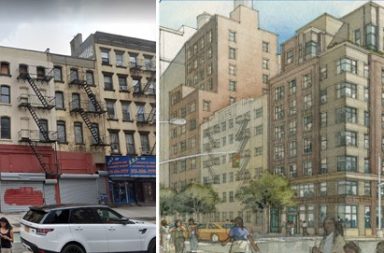

At a seminar hosted by property management company Argo Real Estate at its Midtown headquarters earlier this year, Mazzey discussed the risks of an active shooter and practical ways you and your colleagues can keep safe during such an emergency.

The NYPD advocates an ABC policy: A for avoid the situation; B for barricade and hide; and, as a last resort, C for confront the shooter.

Whoever calls 911 should always provide the location first, Mazzey advises, and then let the dispatcher know there is an active shooter at the office. While you are explaining the rest of the details, the dispatcher will already be sending officers to the building.

In the past, area beat officers were only able to secure the street and wait for an emergency services team to show up. Now, since over 20,000 NYPD officers have been trained to handle active shooters, once four officers are together at the site they are permitted to enter the scene.

“We are fortunate in New York City,” Mazzey says. “When any kind of shot is fired, we have, on average, a three-minute response time from a call to officers on scene. That’s pretty good.”

Meanwhile, those waiting for help need to take action. In some incidents, exits may be blocked by the shooter, so you have to move to step B. To barricade an office, Mazzey advises piling thick, heavy pieces of furniture against the door. Filled file cabinets, copy machines and desks can provide some cover if any shots come through a door (which likely won’t stop any bullets itself).

“Cover,” or an environment that may be able to stop bullets, is different from “concealment,” which merely means a spot to hide that won’t necessarily stop a bullet.

To prepare for emergencies in office buildings, rooms such as tiled bathrooms with heavy metal doors or even computer rooms can be fitted out as safe rooms. The addition of a simple slide lock can provide added protection to keep a shooter out. Ideally, these rooms should also have first-aid emergency kits, communication devices and panic buttons.

While an active shooter event may be over in an average of seven to 11 minutes, Mazzey says it may feel like an eternity and have consequences that last a lifetime.

The NYPD also advises companies to practice various emergency evacuations. “We havemoved forward with some retrofits at our main office in order to provide a safe space for our staff in the event of an active shooter situation,” says Argo Real Estate’s vice president, Marina Higgins, who attended Mazzey’s seminar. “We also continue to educate our staff — both in our managed properties and offices.”

Mazzey’s briefing was part of the NYPD’s Shield program, which partners its Counterterrorism Bureau with private security managers at area buildings. It provides information on worldwide terrorist events, workshops and conferences hosted by senior NYPD personnel. The active shooter program is part of NYPD Shield’s outreach efforts to help the private sector become more prepared for what can become

scary and terrible events.

In 2010, the counterterrorism unit came up with a free active shooter guide available to download from the NYPD Shield Web site. A new edition is due out soon.

Along with advice for companies on how to make plans and practice with drills, the guide includes brief descriptions of around 100 active shooter incidents around the world, how and why they unfolded, and the details of how many people were killed or injured.

During these incidents, an average of 3.1 people are killed and 3.9 people are wounded. “People are going to get hurt, and people are going to die,” Mazzey warned in one of the most sobering moments of his two-hour seminar.

Mazzey himself is a veteran of several Middle East conflicts and a former transit cop who has been with the Counterterrorism Bureau for the last 11 years.

According to the Department of Homeland Security and other federal agencies, the definition of an active shooter is “an individual actively engaged in killing or attempting to kill people in a confined and populated area.”

“The one thing we can do to protect ourselves is be prepared and have situational awareness. Learn how to think outside the box.”

– Officer Christopher Mazzey, NYPD Counterterrorism Bureau

It’s what Mazzey calls, “Anybody trying to kill anybody anywhere.”

But if the NYPD used that rubric, there would be hundreds of city shootings per year. Therefore, the NYPD excludes cases that do not extend beyond an intended victim. It also excludes attacks without a firearm, those involving gangs, domestic abuse, drive-by shootings, robberies and hostage-taking.

The key to defining an active shooter situation, Mazzey explains, is that it becomes random. It might take place at your workplace, for instance, and start out with a specific target.

Sometimes, an employee who was fired may start to come after a supervisor, a coworker or someone from human resources. But as the event starts to unfold, the shooter’s actions and the targets become random.

According to government statistics, about 99 percent of active shooters are male. Sometimes the altercation starts as a domestic quarrel with one target, such as an estranged wife, whom the shooter decides to confront at her workplace. But the incident may quickly spill over to involving her coworkers.

“The one thing we can do to protect ourselves is be prepared and have situational awareness,” Mazzey says. “Learn how to think outside the box.”